[Note that this is a critique of the full game, and contains plot spoilers.]

I am not much of a platformer guy. Except for Mario Galaxy, I haven't really engaged with one in years. Nor am I, since the mid-90's, much of an adventure/puzzle guy, aside from indulging in a few of Telltale's Sam & Max episodes, and of course Portal. Hell I'm not even much of an indie games guy, as something is lost on me in that more abstract realm. But Braid, the new indie puzzle platformer by Jon Blow, grabbed my attention and spoke to me despite my lack of usual interest in the bounds it occupies.

What's most interesting to me about Braid is how it takes familiar mechanics, considers their implications, and then twists them into an effective metaphor expressed through the play itself. Video games it's based off of such as Super Mario Bros. have always pointed towards a cartoon representation of the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics: each of the player's "lives" represent one possible set of decisions Mario might have made; dying and trying again presents a vision of an alternate reality where Mario made a different decision at some crucial point. The one reality that finally leads to the completion of the game is made up only of the lives with which the player made progress past at least one save point, building towards a whole.

Braid takes this interpretive aspect of an existing game format and makes it integral to the overall experience. The player may rewind time at will, throwing the sheer number of alternate realities onscreen into sharp relief. The narrative of the game is expressed through interstitial text relating the story of a man's struggles between maintaining a romantic relationship and pursuing some other, obsessive goal. The seeming regret and misgivings of the protagonist "Tim" in these passages highlights the difference between the endless revision possible in a video game, and the inability to take back permanent life decisions in the real world. The play and the narrative come together to portray the longing and impotence of a man wishing to undo the past. The way the mechanics of the game reinforce this aesthetic theme is wonderfully subtle and fully realized.

The place that this dichotomy falls down is when Blow's reach surpasses his grasp in the epilogue of the game. Mechanical play is well-suited to supporting universal and personal themes such as the ones noted above, and to this end the protagonist's story of love and loss retains meaning when told as a parable. But at the end of the game the narrative content becomes overly weighty and specific, calling out the creation of the atomic bomb and other major scientific and intellectual conundrums by name-- conceptual territory of a fidelity and gravity that the play of Braid can't support. I don't begrudge Blow an attempt at addressing important issues, but the weight of the atomic age seems too much to satisfy with a few lines of text that feel incongruous with the rest of the production. If this aspect of the narrative were going to be present at all, I wanted it reinforced by the gameplay, as the rest of the framing story was; instead, I came away thinking, "Wait, was that supposed to be about the atomic bomb somehow?" This overextension of narrative ambition without satisfactory justification did a disservice to all of the game's other highly successful elements.

As a puzzle game, Braid is nearly flawless. On top of reversability, time works differently in each of the game's worlds, and in each these new mechanics are fully explored. It's a joy to be learning new things along every step of the game. But like most puzzle games, it's a tightly authored experience, with only one solution to any given room: while all the puzzles are set up in extremely clever ways and are largely discoverable to the attentive player on first pass, the puzzles definitely tend away from making the player feel smart for deciphering them and more towards making the player feel like Jon Blow was smart for coming up with them.

To be playable at all, the rules of a game's world must be internally consistent at all times, and Braid is no different. So, the only places that the play of Braid falls down are where Blow breaks his own rules. For instance, it's understood that every puzzle room of Braid is solvable first time through, on its own as a distinct unit. So, when the player must leave a room in World 2 without collecting all the puzzle pieces, then come back later to grab them, it's frustrating and unfair since it's the only place that this rule of Braid's structure isn't upheld. Elsewhere, puzzle solutions require an understanding of the world's properties that haven't been demonstrated up to that point. How am I to know that elements of a completed puzzle can become interactive pieces of the gameworld? Or that an enemy bounces up into the air when it lands on my head? Additional training simply to introduce all the pertinent game dynamics would have reduced the 'unfair' challenge of the game without reducing the fair challenge of figuring out how all those elements fit together to solve a given puzzle. In the end though, these are small quibbles directed towards an outstandingly unique and satisfying puzzle game.

Braid is a brilliant exploration of a principle that Blow has addressed in his prolific conference talks: certain game genres have been prematurely left by the wayside, victims of the ongoing march of technology. There are many formats ripe for reexamination outside the existing assumptions built before they fell out of favor. What if progress in a platformer weren't gated by having to replay segments whenever the player died? What if the challenge weren't in outright manual dexterity and memorization but in mental dexterity and logical deduction? What if the many-worlds quantum aspect of retrying platformer segments were embraced, wound into the play, and made meaningful to the player on multiple levels? What if we went back and picked up design threads that we'd dropped along the way, and found that they still had plenty more slack to explore? It's a way of stepping out of the technological jetstream and embracing a sustainable sort of design that's conscious of more than the medium's here-and-now. One might say it's a method of exploring an alternate path that one branch of game design might have taken, if only we could go back in time and try again.

8.17.2008

Quick Critique: Braid

8.12.2008

Magazine

This month's issue of Official Xbox Magazine (with Fable 2 on the cover) contains a lovely little write-up of 2K Marin (including a team photo where you can see my smilin' mug.) Like the cover says, meet the minds behind BioShock 2! Nice being in print. On newsstands now.

Edit: I just noticed that every single game mentioned on that cover is a sequel.

7.27.2008

Being There

I've been thinking a bit about the strengths of video games as a medium, as well as why I'm drawn to making them. One colors my perception of the other I suppose. But in my estimation every medium has its primary strength.

Literature excels at exploring the internal (psychological, subjective) aspects of a character's personal experiences and memories.

Film excels at conveying narrative via a precisely authored sequence of meaningful moments in time.

And video games excel at fostering the experience of being in a particular place via direct inhabitation of an autonomous agent.

Video games are able to render a place and put the player into it. The meaning of the experience arises from what's contained within the bounds of the gameworld, and the range of possible interactions the player may perform there-- the nouns and the verbs. Just like in real life, where we are and what we can do dictates our present, and our possible futures. Video games provide an alternative to both the where and the what of existence, resulting in simulated alternate life experiences.

It's a powerful thing, to be able to visit another place, to drive the drama onscreen yourself-- not to receive a personal account of someone else's experiences, or observe events as a detached spectator. A modern video game level is a navigable construction of three-dimensional geometry, populated with art and interactivity to convincingly lend it an identity as a believable, inhabitable, living place. At their best, video games transmit to the player the experience of actually being there.

Video games are not a traditional storytelling medium per se. The player is an agent of chaos, making the medium ill-equipped to convey a pre-authored narrative with anywhere near the effectiveness of books or film. Rather, a video game is a box of possibilities, and the best stories told are those that arise from the player expressing his own agency within a functional, believable gameworld. These are player stories, not author stories, and hence they belong to the player himself. Unlike a great film or piece of literature, they don't give the audience an admiration for the genius in someone else's work; they instead supply the potential for genuine personal experience, acts attempted and accomplished by the player as an individual, unique memories that are the player's to own and to pass on. This property is demonstrated when comparing play notes, book club style, with friends-- "what did you do?" versus "here's what I did." While discussing a film or piece of literature runs towards individual interpretation of an identical media artifact, the core experience of playing a video game is itself unique to each player-- an act of realtime media interpretation-- and the most powerful stories told are the ones the player is responsible for. To the player, video games are the most personally meaningful entertainment medium of them all. It is not about the other-- the author, the director. It is about you.

So, the game designer's role is to provide the player with an intriguing place to be, and then give them tools to perform interactions they'd logically be able to as a person in that place-- to fully express their agency within the gameworld that's been provided. In pursuit of these values, the game designer's highest ideal should be verisimilitude of potential experience. The "potential" here is key. Game design is a hands-off kind of shared authorship, and one that requires a lack of ego and a trust in your audience. It's an incredible opportunity we're given: to provide people with new places in which to have new experiences, to give our audience the kind of agency and autonomy they might not have in their daily lives; to create worlds and invite people to play in them.

Kojima has said that game development is a kind of "service industry," and I think I know what he means. It's the same service provided by Philip K. Dick's Rekal, Incorporated: to be transported to places you'd never otherwise visit, to be able to do things you'd never otherwise do. As Ebert says, "video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control." I'll not be the first to point out that this is an astute observation, and one that highlights their greatest strength: video games at their best abdicate authorial control to the player, and with it shift the locus of the experience from the raw potential onscreen to the hands and mind of the individual. At the end of the day, the play of the game belongs to you. The greatest aspiration of a game designer is merely to set the stage.

[This post was referenced in Jonathan Blow's talk "Games Need You" at this year's Games:EDU South conference in Brighton, England.]

7.13.2008

Japanese: redux

Happy news!

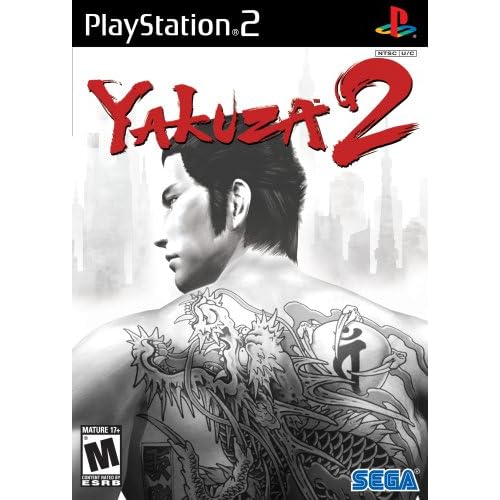

Some time ago, I wrote of my disappointment that Sega was replacing the Japanese voice track in their North American release of Yakuza with a Hollywood voice cast. I ended up playing the full game eventually and did find navigating the world of Yakuza engrossing, but the incongruous voice track left a tarnish on the experience overall.

So, I was excited to read in the current issue of EGM (verified by Sega's official product page) that Yakuza 2's North American release will feature the original Japanese voice track with English subtitles! My guess is that the decision was less artistically-minded than simply pragmatic: I assume that the investment in an English voice cast for the first game didn't pay significant dividends, and with the sequel landing well into the PS2's final hours (not to mention the niche appeal of its subject matter) it's pretty much guaranteed to sell modestly at best. So, market forces and artistic cohesion happen to coincide here, with the most economical production approach resulting in the best end-user experience. Cool. I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

7.06.2008

Stubborn

Via a link on Jonathan Blow's blog today, I played through lo-fi indie game Flywrench. My clear time was 01:02:53. Which is kind of a miracle, and highlighted something odd about 'hardcore' gamers: we can't help but show computers who's boss.

It's weird! Flywrench is a sadistically difficult game, requiring perfect timing, some luck, and a whole lot of patience. To its designer's credit, the game allows you to instantly retry each time you fail, and fail I did-- hundreds of times certainly within that hour and two minutes, sometimes with infuriating frequency.

But I pushed on, determined, for some reason, to best the machine. The game is balanced and designed well enough that each time I failed, I acknowledged that it was my own fault-- my keypress wasn't precise enough, my analysis of the playfield's current state wasn't accurate enough, my understanding of the physics simulation wasn't clear enough. Each time I failed, even as the droning, dissonant soundtrack squealed in my ears, daring me to quit, my determination to master the inputs and pass the game's challenges grew.

And after an hour and two minutes of frustration and anxiety interrupted occasionally by glimpses of elation, I'd achieved what? I saw the credits. I received a readout of my completion time. I got an error message upon trying to close the executable. And it was over.

The graphics were sterile and abstract, functioning only on the symbolic level. The narrative was mildly surreal and led up to a kind of clever joke, but wasn't even a factor in why I was playing. It was the implicit challenge: man versus machine, me versus a digital, unknowing system of rules that didn't care whether I played it or not. But I had to finish the game, practically out of spite. I was proving to the game itself who was boss, or I guess in actuality I was proving to myself that I could do it. Because really, it was just between me and a bunch of numbers. Intellectually, I know that the game was tuned by a person to be just difficult enough to egg me on, but not quite to the point of being impossible. I was being manipulated. And it worked. I wasn't going to let this game kick my ass.

It's so absurd, I don't even know where the compulsion comes from! It's finishing Super Mario Bros. alone in your room at age 8, or completing some punishing, poorly-designed Sierra adventure on your IBM compatible, or 100-percenting Through the Fire and Flames on Expert. It's beating Contra without the 30 lives code, getting to the kill screen on Donkey Kong, finishing a Metal Gear Solid game without being detected, beating Ninja Gaiden on its hardest difficulty setting (or hell, beating the NES version at all,) or completing The Legend of Zelda without picking up any heart containers.

I can see it from the uninitiated viewer's perspective: why do you put yourself through all this anguish just to complete a video game? It doesn't sound like you're having fun. What's the point? Nobody's going to give you a medal, and it's sure not helping cure cancer. Don't people play games to relax?

I don't have a good answer. I don't know why, when this dumb little game pushed me down and stood over me, squelching its little noises and sending me back to the start of the level, I kept getting back up and trying again. But I did it, and I showed the program I'm better than the best it had to offer.

Why do we feel the need to beat the game? Because it's there.

Call to Arms entry 14: Peace

Animator Christiaan Moleman submits a series of interactive vignettes to the Call to Arms, a selection of ground-level perspectives on the conflict in Gaza.

Call to Arms 2008 - “Peace”

A game of interactive vignettes set in and around Gaza, showing several different non-chronological perspectives in 1st person, not unlike Call of Duty 4: a Palestinian child throwing rocks at a tank, an Israeli soldier on patrol, a paramedic, a Western journalist, and others…

It begins and ends with a suicide-bombing in a cafe. The first time you are a mother with her daughter. The second time, you are the suicide-bomber. Cut to black at the crucial moment, or fade if you walk away.

Open on a crowded cafe. You are sitting in a wooden chair on the far side of the room, sunlight hitting the checkered floor through the door behind you. Still morning. You gently sip your coffee. Next to you is a little girl playing with the ice cubes in her empty glass. With the glass in her hand she looks up and smiles.

You pat her on the head.

There’s a half-eaten sandwich on a plate in front of her, with little teeth-marks.

You gesture towards her to eat the rest of it. Reluctantly she takes a bite.

She freezes. When you turn to follow her gaze and look behind you, you see a man enter the cafe. In his hand is a small device. You turn to your daughter and hold her. The man screams something.

CUT TO BLACK

Putting the player in the shoes of different characters might inspire some empathy for the people actually living through this conflict and reflect on the grief it causes to both sides.

Gameplay varies with each perspective: mother interacts affectionately with her little girl, kid tries to throw as many stones as possible without getting hit by stray bullets, paramedic tries to keep a bombing-victim alive for the duration of an ambulance ride, soldier explores cautiously, journalist tries to get coverage of a shoot-out without getting killed, and so on…

Would be a fairly linear affair, with specific interactions up to the player. There should be choice when it matters, but never transparently so. The player should do what he thinks he has to within the confines of the game mechanics rather than press A for ending 1…

The game should be no more than 30 to 60 minutes long so as not to diminish its impact. The Nintendo Wii could be a good platform as it’s shown itself well-suited to extremely varied interactions, though more conventional control-schemes could also apply and some degree of production value would be necessary to sell the character empathy.

--Christiaan Moleman7.02.2008

Conservatism

According to Eurogamer, "Fallout man" Ashley Cheng (allow me to introduce myself, I'm "BioShock man" Steve gaynor) has asked forgiveness for saying in his personal blog that he's disappointed that the design of Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2 look "conservative."

It's one sad-ass day when somebody has to present a mea culpa for calling a spade a spade. The low-level mechanical changes and additions might be debated by hardcore fans, but to the uninitiated viewer, Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2 are outright continuations of the same 2D isometric games I was playing in high school. They might have smoother gameplay, the character models and environments may be rendered in three dimensions and have fancier particle effects, but on an experiential level these are games expressly for the existing fanbase: safe, predictable qualitative refinements in mechanics and presentation, the most conservative possible approach.

The funny thing is, the closest comparison to this situation that I've considered is the game Cheng is currently working on: Fallout 3 could have taken an incredibly conservative approach if it had gone into production as the isometric-3D direct continuation of Fallout 2 that was once under development by Black Isle. That might have satisfied the entrenched, but I'm personally glad to see Bethesda's Fallout 3 trying to create a new, different, more personal experience out of the Fallout universe. How successful any of these projects will turn out is yet to be seen, but I know which has piqued my interest, by virtue of eschewing conservatism.

7.01.2008

Call to Arms entry 13: Fruit of the Womb

Roberto Quesada submits a Call to Arms entry which challenges the player to balance human relationships and material success in a world over which he in fact has very little control: the monopolistic corporate stage of the 19th century.

Starting a new game brings the player to a standard character creation screen: The player chooses what the character looks like, and a certain amount of points will be alloted for distribution amongst various attributes (intelligence, charisma, et c.) and skills (dueling, culinary sauces, et c.), with the distribution of points among the former affecting the weight of points distributed among the latter. The actual attributes and skills present in the creation menu are not important; any game play that would ordinarily depend on these variables will be almost exclusively real-time and depend on the player's own skill, but this will not be made apparent in any way.

After the character is created, the player will form a backstory and mission statement of sorts. The formulation of a backstory depends on the player choosing from various items that make up the history of the family business. All elements here will be generic in nature; for instance, instead of choosing “You're the heir to a steel company,” the player chooses from options such as “You're the heir to a knick knack company.” The instruction manual (or contextual pop-ups) will detail certain aspects of “knick knacks” and “doodads” in an effort to mislead the player into thinking there are nuances that do not actually exist in the game (a history of the materials, a technology tree, popularity of certain items among certain demographics); in reality the way certain products behave or perform will be set mathematically by the game as it progresses (see below). The backstory will also consist of how the family came to its position of power, among other such details, leading the player to believe these variables will affect game play (they most certainly will not).

The mission statement will have a “significant” bearing on game play, as it will be the framework by which the player's “success” is calculated. As part of the process, the player will choose what he most wants to accomplish from goals such as influence, wealth, and notoriety. All goals will be interconnected; the player chooses what he cares about more, with a limited number of things-you-care-about points available for distribution, and the scale created will affect a successometer viewable during game play.

In terms of actual game play, Fruit of the Womb is more or less a sandbox game. It can be first- or third-person, the player interacting with the environment by means of a hand cursor, à la Black & White or that one game that's very dark and requires you to walk around with a flashlight and search through desks. The player has a job as the head of his company, but can delegate nearly all related tasks due to seniority. On the other hand, he has a son or daughter who can be similarly micromanaged or ignored. There is a base level of wealth below which a player can never fall; insuring the funds necessary to delegate the raising of his son: private/boarding school, au pair, military school, whatever. The son's regard for the player/father depends largely on how he is raised, but it is not mechanical or predictable (see below). The player can also directly raise the son by taking time off from work and interacting directly. Via the cursor, the player can smack around or reward his son as he sees fit. He can take his son hunting, or to the zoo, or to a prison for a Scared Straight!, 19th Century Edition-style education. The idea is to give the player ultimate freedom, the likes of which it would be burdensome to describe here, without straying too far from the son/business focus of the game; i.e., the player can somehow be artificially bound to these aspects of game play, but within them he is totally free: if he wants to go downstairs while at work and shoot his accountant in the face, such is his prerogative, though realistic consequences would follow. The player's actions in life will also affect how he is perceived by his son.

In addition to misleading the player with regard to basic gaming conventions, the way the business world and the player's children behave are somewhat randomly determined at the start of the game, with smaller variations occurring as the game progresses. Business trends will follow random occurrences in the game's history, but in an unpredictable way. And when the player's wife pops out a child, the child's personality is randomly defined within the bounds of a loose algorithm created to keep the child's behavior within the realm of reality. The personality will determine how the child responds to being sent to a military academy as opposed to being coddled: will he resent his father more for perceived neglect or for being raised as a nancy boy without the skills necessary for running the family business with an iron fist? There is no way of knowing anything until a route is tried.

The player can also have daughters. Daughters may be groomed in the exact same fashion as sons, but are much more difficult to maneuver into a position of respect within the company as per the societal norms of the proposed historical period. The more children the player has, which is mainly limited by a nine-month gestation period, the more people are vying for power within the company (or not giving a shit, depending on their personalities); this can lead to anything from productivity among the more sycophantic children to patricide. If a player has too many children (the cap is random, within a realistic range), his wife will die, and he will have to engage in a courtship mini game to find a new wife. The wife is little more than a child factory for the player, in an effort to focus the player's affections on his children and business; some wives are stronger factories than others. It's likely that the maximum-children-possible route would never be followed, except for a hearty laugh.

Players' characters grow old and die. The player can then watch time unravel either in real or accelerated fashion. This will allow one to see how things play out indefinitely; though the era never actually changes, the children eventually have their own children, grow old, and die; the player can see how his family and business change. The player is not allowed to continue (“reincarnated” into one of his children, for example) in order to give his actions more weight. He can only start over.

The reasons for the game's unpredictability and sociopathic treatment of the player with regard to his expectations are: 1) To mimic real life and 2) To jar the player. Ideally a game like this would be extremely complicated (on the level of a detailed MMORPG's mechanics, for example, if not greater) in an effort to dissuade the player from attempting to play the game how it “ought” to be played by attempting to max out the successometer, but not so complicated that the player couldn't come up with methods for “success.” This is probably unachievable, but the idea would be to give the game a level of complexity that would require the player to play constantly and attentively (taking his own notes, as the game will not have an automatic notepad or “journal” feature) if he wanted to have success in the manner that the game apparently requires; the game would be tedious and life-ruining but “winnable,” or interesting/entertaining (hopefully) but rewarding on a different level. Note that disregard for the successometer does not mean complete disregard for the business; the player can still groom his son to take over, but just not worry about whether the son will preserve the family legacy to a T. The successometer does not punish, but merely exists. The player can follow his initial expectations or eschew them.

The main theme being explored here is how one's sense of duty forms. The player is deliberately put into a game with certain expectations in an effort to mimic the social stressors that existed in the era; does the player comply merely because there exists an order that the game wants him to follow, or does he ignore the game and form a bond with his child(ren)? Following what's expected is tedious (though maybe not for all people) and results in a gauge filling up; the player can be rewarded with some sort of tokens or with the unlocking of business opportunities the more he keeps his “success” level high. Or does the player pursue a familial relationship with no apparent reward save the relationship itself? Characters would have to be realistically rendered, or at least have realistic responses/emotions, in order for the player to feel some sort of empathy, but pursuing this route, which again would not be presented overtly by the game as a possibility, could unlock more depth to the relationship aspect of the game, making the bond more meaningful as the player pursues this route.

Concerns:

1. Perhaps only a small set of people could actually empathize with the characters of a video game.

2. If this game were made, the concept would eventually be leaked (possibly before the game is even released), in effect making the game meaningless.

3. Misogyny.

6.29.2008

Critique: Haunting Ground

Quite a while back, I was turned on to Haunting Ground by Leigh Alexander's writeup of it for her Aberrant Gamer column on GameSetWatch. Her insightful critical read of the title made me want to see it for myself, but the disturbing subject matter she described kept me from diving in for a long time. And now that I've played through it, I've been taking even longer to write up my experience.

It's because Haunting Ground is a tough game to write about. Half of it's brilliant, the other nearly unplayable; it treads patently unpleasant and distressing territory, but features clever, enjoyable design that can be great fun to play. It uses exploitation and objectification to challenge audience identity and gender expectations in ways that only a game could, but feels simultaneously pandering and puerile. It's a great success, and a great failure. It's a weird game.

Haunting Ground is a Capcom survival horror title of 2005, following in the tradition of the Clock Tower series. The player is cast in the role of Fiona Belli, a young woman who wakes up in a strange castle with vague memories of a car wreck floating in her head. Fiona soon befriends a helpful German Shepherd named Hewie, and with his assistance must navigate through a convoluted series of puzzle rooms while evading the depraved denizens of the castle. The first half of the game is an incredibly well-crafted example of classic survival horror design. The castle itself has a creepy-but-plausible layout which includes bedrooms, sitting rooms, bathrooms, gardens, studies, a kitchen and dining room, along with a number of stranger, more baroque locations such as alchemy labs, a gallery filled with dolls staked to the walls, and a demented merry-go-round. The dense puzzles filling the castle hinge on a distorted abstract logic, and beg the question of just what kind of madman would construct such a lair. The setting layers surreality on top of mundanity with aplomb.

The first half of the game is an incredibly well-crafted example of classic survival horror design. The castle itself has a creepy-but-plausible layout which includes bedrooms, sitting rooms, bathrooms, gardens, studies, a kitchen and dining room, along with a number of stranger, more baroque locations such as alchemy labs, a gallery filled with dolls staked to the walls, and a demented merry-go-round. The dense puzzles filling the castle hinge on a distorted abstract logic, and beg the question of just what kind of madman would construct such a lair. The setting layers surreality on top of mundanity with aplomb.

Mechanically, the clues and solutions to the first half of the game's tightly-knotted puzzles are wonderfully decentralized and satisfying to solve. Much like the dreamworld of Silent Hill 2, Haunting Ground's early puzzles operate on an otherworldly but readable ruleset which begs nonlinear thinking from the player.

The gameworld's structure and puzzles encourage the player to constantly make connections between distant points, while providing just enough direction to keep the player from getting completely lost: the clue to any given puzzle always lies in one room, while a pertinent object lies in another, and the place the puzzle must be completed in another still, resulting in puzzle solutions that sketch complex webs across the playable space.

The castle is divided into distinct chunks composed of a dozen or so rooms apiece, each chunk initially blocked off from the other by doors "locked from the other side." As the player enters a new chunk, he builds a mental map of that isolated physical space, then by clearing obstructions unlocks the blocked doors to prior sections, gradually building out the full map of the castle as a whole. From the nonlinear objectives to the physical shape of the gameworld and the player's course of progression through it, the first half of Haunting Ground presents a wonderful mechanical experience centered on completing circuits within a system driven by interconnectivity.

The character dynamics and narrative frame that buoy the gameplay in the first half of Haunting Ground are equally compelling and challenging, in totally different ways. Filling the role of Fiona Belli places the player in limbo between voyeur and subject, exploiter and exploited, violator and violable, and for most players, between masculine and feminine. It's a distinctly tense space to occupy, and can only arise from the play of a video game, as opposed to passively observing other entertainment media.

We first see Fiona in Haunting Ground's attract screen movie, padding down a long, red corridor wrapped in a translucent bedsheet, intercut with footage from a camera that follows a blooddrop trickle down the contour of her nude body:

The symbolism makes itself clear here, and colors the game's ongoing depiction of Fiona, which emphasizes her femininity, vitality and vulnerability. These aspects of the protagonist drive all of the ongoing narrative and secondary character motivation in the first half of Haunting Ground, which finds a pitiable rogue's gallery chasing lustily and relentlessly after Fiona. She is expressly designed as an object of desire.

In an early scene, Fiona trades in her wispy bedsheet for a set of clothes she finds disconcertingly laid out on a bed as if for an expected guest, and which furthermore seem to be tailored just for her. As she dresses, we observe the scene through the eyes of an unseen figure watching from behind a painting hung on the wall; we are momentarily put in the shoes of someone preying on Fiona, while simultaneously charged with keeping her from harm's way. The clothes she's been given are exploitative and degrading: a skirt much too short for decency, a bodice cut too tight for modesty, bringing into question the motives of her gracious host. But meanwhile, the game's developers also intentionally invested in a system for simulating breast-bounce as Fiona moves about the castle. The revealing costume serves a fictional purpose as an outfit orchestrated by Fiona's perverse captors, but the computational power poured into depicting boob jiggle can serve no one but the (predominantly male) developers and players of the video game. The overall effect is to reinforce Fiona's vulnerability as a captive subject within the gameworld, while also indicting the player as a voyeur in league with the story's antagonists.

Fiona is hereafter imperiled by the ongoing threat not just of death, but of vague and looming bodily violation. Her first pursuer is a hulking manchild referred to as "Debilitas," seen in the attract screen movie above. When he initially encounters Fiona, he glances from a filthy ragdoll he's holding, to our protagonist and back, then tosses the doll aside and lurches after his new object of desire. As Fiona progresses from room to room, Debilitas will attempt to chase her down when their paths cross. During the pursuit he'll shout out "Dolly!" giggling and stomping with child-like delight, but also sometimes stop to paw at the crotch of his pants in frustration. The implication is that his adult body and stunted mind may be in conflict: the player gets the feeling that Debilitas wants to rape Fiona when he catches her, without even understanding his own actions. The dissonance between physical and mental intent places the ongoing cat-and-mouse game between the threatening-but-blameless Debilitas and the helpless Fiona in an exceedingly uncomfortable frame. If Debilitas embodies the conflict between male and female, lust and innocence, brawn and intellect, Fiona's second pursuer, Daniella, explores a range of conflict between two female forces: sensation and function, humanity and inhumanity, servitude and dominance.

If Debilitas embodies the conflict between male and female, lust and innocence, brawn and intellect, Fiona's second pursuer, Daniella, explores a range of conflict between two female forces: sensation and function, humanity and inhumanity, servitude and dominance.

Daniella is the maid of the castle, and takes over as Fiona's pursuer when Debilitas steps down. She reinforces one of the ongoing themes of the narrative frame, which deals with alchemy and reanimation. As the game progresses, it becomes clear that Daniella is an automaton: she has a body and sentience, but no humanity. As she says, she is "not complete," and can't "experience pleasure or taste." Daniella's turning point from observer to pursuer comes when we find her running her hand over Fiona's body as the girl sleeps, her palm coming to rest over the womb. As Fiona awakes, Daniella goes on to study her own reflection in a window, then bash her head against it in disgust until it shatters, from which point forward she mechanically follows Fiona around the castle, wielding a huge shard of glass as a blade.

Unlike Debilitas, Daniella isn't after Fiona due to any physical urge, but out of jealousy, confusion and contempt. Daniella covets everything Fiona represents: her vitality, her fertility, which spring from her femininity and youth. Daniella has no youth because she has no age; she's an empty shell and she knows it: simply being reminded of such by her own reflection drives her over the edge. When her polar opposite arrives in the form of Fiona, she simply can't process the contrast. Daniella is associated with dolls and puppets via mise en scene throughout the castle, and is just that: a body without a soul, a tinman without a heart. She is broken, pitiful, and terrifying. The most unsettling aspect of Fiona's predicament is the vagueness of the threat that looms over her. If she's caught by Debilitas, what is he capable of? What is Daniella's true nature? And who is the madman orchestrating all the events in this demented castle anyway? Dolls, mannequins, puppets, earthen golems, mummified girls and even partially reanimated corpses occupy room after room; what is the obsession with life from death?

The most unsettling aspect of Fiona's predicament is the vagueness of the threat that looms over her. If she's caught by Debilitas, what is he capable of? What is Daniella's true nature? And who is the madman orchestrating all the events in this demented castle anyway? Dolls, mannequins, puppets, earthen golems, mummified girls and even partially reanimated corpses occupy room after room; what is the obsession with life from death?

At one point, Fiona's unseen host, a mysterious hooded figure known as "Riccardo," tells Fiona to remove the tarp from a form sitting on a couch in the study. Upon pulling back the sheet, Fiona finds a clay replica of herself in a state of full pregnancy. Just what the hell are these people's intentions? Overtones of Rosemary's Baby intensify. While the player wraps his head around the castle's abstract puzzles and flees from an array of freaks, an abiding, oppressive fear of the unknown always looms large over the proceedings. It's the opposite of the explicit threat of having Leon's head chainsawed off in Resident Evil 4. Does Fiona face a fate worse than death? Not to know is to dread it all the more.

Haunting Ground chooses a female protagonist deliberately, almost perversely. Unlike many games that put an attractive female shell on an otherwise genderless protagonist, Haunting Ground exploits the trope of the woman imperiled in a way only video games can, twisting it to overlap with the player, resulting in a strange duality that requires the player to really delve in and inhabit the role, to identify with the uniquely female aspects of the character and be driven by her fear and vulnerability, as opposed to observing from a detached viewpoint. The player of the game is charged with protecting Fiona, but also with being Fiona, a character who is different from the player in much more psychologically significant ways than your standard video game protagonist. It's a unique experience for a male player, and uncomfortably so, but one worth braving for its truly alien qualities. Both as a set of engaging game mechanics and as a novel and affecting transportive experience, the first half of Haunting Ground is an overwhelming success.

But here's the thing though:

The second half of Haunting Ground takes every aspect that made the first half interesting or enjoyable and turns it absolutely on its head. Once the third of four acts begins, puzzle design devolves almost instantly into a linear set of rote objectives, with no thought or deduction required. The areas thin out and transition from unsettlingly surreal to simply goofy and implausible. While the early acts had me making interesting mental connections and criss-crossing the map to clear obstructions, successive acts had me simply walking from room to room pressing the buttons in the order I was instructed, or worse yet participating in terribly-designed boss fights.

Player feedback, which was a point of emphasis in the first half of the game, takes a nosedive: I banged my head against one bossfight for the longest time because using the "come here" command on Hewie seemed to be resulting in an aggressive attack that I was just mistargeting, while in fact a FAQ revealed that I had to use the "attack" command explicitly to achieve my goal, while nothing in the game even pointed out that I was making a mistake in the first place. I solved another puzzle by sheer coincidence: one progression gate requires you to simply have a candle in your inventory while your pursuer follows you into a room which also contains some dynamite, at which point a cinematic plays, solving the puzzle for you. Thank god I hadn't actually been trying to figure that one out in any kind of intentional fashion. The final sequence in the game is horrifically punishing, obtuse, and just awful: an invincible boss that kills you in one hit chases you through a gauntlet, requiring the player to restart over and over, scouting with death to build enough precognition to perform the routine perfectly, lest the "game over" beast catch up to you for the dozenth time. The abruptness with which the quality of the game design drops off after the second act is striking, and it continues plummeting all the way til the final credits roll.

Furthermore, any subtlety or restraint the game showed regarding its themes is sandblasted away. We go from uncomfortable sidelong allusions to reanimation, fertility, and impregnation, to Riccardo shouting in the player's face, "Your father and I are clones! WE.. ARE.. CLONES!!" and yelling outright, "Fiona! Let me into your womb!" The story, which pointed in an intriguing direction in its early stages, descends into silly nonsense along with the gameplay self-destruction. We see clones floating in green goo tubes, Riccardo makes himself invisible by casting some spell on Fiona's eyeballs, and we meet an ancient alchemist named Lorenzo who falls from his wheelchair and scrambles along comically behind Fiona, flailing his arms in triple-time, practically begging for strains of Yakkety Sax to play in the background. Everything foreboding and unsettling about the game's narrative frame is transformed, alchemically, into its polar opposite: laughable, eye-rolling camp.

So, Haunting Ground is a game that I can recommend emphatically, up to its halfway point. Buy a used copy of the game for cheap and play up through the end of Daniella's chapter, then turn off the PS2 and don't look back. Despite the second half's implosion on every level, I completed it out of respect to what a great game the first half was, and out of some vain hope that the conclusion would make my devotion worth it. It wasn't worth it though, except to be able to report with confidence that you definitely shouldn't do the same.

Haunting Ground isn't pleasant. It isn't uplifting. Hell, it isn't even noble or progressive, considering its queasily pandering depiction of its protagonist. But its first half is incredibly well-crafted and entrancing while it lasts. At its best, Haunting Ground will take you to an unfamiliar place, ask you to put yourself in a pair of shoes that are particularly difficult to wear, and to experience all that comes along with that challenge. Good luck.

6.24.2008

Call to Arms entry 12: Bereavement in Blacksburg

Manveer Heir, designer at Raven Software, writer of the Design Rampage blog, and weekly columnist for GamaSutra, contributes a Call to Arms design based on his personal reactions as an alumnus to the Virginia Tech shooting incident of 2007. Please visit his original post on Design Rampage for a thoughtful preface and conclusion to the outline.

You begin the game laying in bed, early in the morning. The phone rings and goes to message. It's your girlfriend's voice and she's asking you to answer and talk with her. It is apparent from her dialog that you knew someone directly killed in the attacks. For obvious reasons, who that person is isn't revealed, nor is it relevant.

Once the message finishes, you take control of the character. From here the world is rather open. There are multiple objects to interact with in the opening room. You can use the phone to call your girlfriend back. You can use your computer and see e-mails from the administration, as well as condolences from friends. You can watch TV or listen to music to escape from things. You can turn to bottles of alcohol to drown your sorrows. Or you can just leave the room and venture to other parts of campus and find other interactions. The choices are yours and they affect the way your character progresses through the game.

Getting drunk and then talking to your girlfriend may cause you to speak in a belligerent or flippant manner. It may also make certain choices unavailable to you later, such as going to the school's convocation with her later. Speaking to her sober may open up a dialog that wouldn't occur otherwise, one that may have the character ultimately express his true feelings verbally.

Internally, the game keeps a “grief score”. You start at zero, and positive influencing interactions will increase this score and negative influencing actions will decrease it. However, the player is not aware of this scoring mechanism. In my experience, often during the grieving processes we do not see the whole picture of how our actions can positively or negatively affect us. Hiding the true outcome of different interactions helps proceduralize that state of mind.

The player has an idea that drinking isn't probably the best idea, however they may not realize how bad of an idea it may be. Additionally, this means different actions can have different values depending on the circumstances surrounding it. Using alcohol again as an example, drinking alone may be negative but drinking in moderation, with friends may be neutral or even positive.

As you leave your room and explore more of campus more interactions are available. You can write your thoughts in your journal or compose music that expresses your feelings. You can attempt to go on with life as if nothing is wrong, by just doing normal everyday things such as going out to dinner. You can stop going to classes, once they resume. You can visit the memorial erected to the victims. There are many possibilities available.

All of these minor interactions will force scripted major events, depending on your “grief score” at the time. The minor interactions of beginning to drink and never answering your girlfriend's phone calls may result in the major event of her breaking up with you. The minor interactions of regularly writing in your journal and communicating with others can lead to the major event of moving to the next stage of grief.

Ultimately, there should be multiple paths to end the game, just as there are in life. One can move through all the stages of grief, or become stuck at certain stages. The needs to be a clear end to all narrative paths. In the end, the game is one of choices and how these choices ultimately affect how we deal with grief.

My concerns with this design are numerous. Are there enough interactions available to make a meaningful experience out of? How does one define what are positive and negative choices? One person's positive choice could be another's negative. Also, does this actually help the player understand the grieving process or does it rely too heavily on narrative to push this feeling and just have simple interactions as the way to branch that narrative?